I’m excited to bring you the 20th (!!!) Slow FI interview! It seems like yesterday that I published the first interviews featuring Wanderlust Wendy, Michelle from Frugality and Freedom, and Josh Overmyer.

I had no idea that the idea of Slow FI would catch on within the FIRE community. I feel lucky to have the opportunity to amplify so many stories of people who are using their financial freedom to design a life they love today.

This interview comes from David who writes the blog CityFrugal. David and I started blogging around the same time, and I identified with his story right away.

We both have gone against the traditional FIRE narrative that tells you to live in a low cost of living area. David lives in one of the most expensive cities in the world, New York City.

Along with David, we have found that it’s more than possible to pursue FI in a large city. Many people assume that living in a high cost of living area would hinder our path to FI. We’ve actually found that it accelerated both our path to FI and our happiness.

Not only does David defy this aspect of the traditional FIRE narrative, but he’s also a huge proponent of improving your life today along the way to FI.

Let’s get into David’s story!

1. Tell my readers a little bit about you.

I’m David. I’m a strategist, bookworm, amateur woodworker, and writer of a blog called CityFrugal. I’ve been pursuing financial independence for the past seven years while living in some of the most expensive cities in the world – San Francisco, Toronto, and New York.

Most financial independence advice tells you to steer clear of cities. People think it’s impossible to save money there. I decided to challenge that wisdom. By thinking strategically and conducting tons of experiments, I’ve been able to save between 25% and 47% of my income each year.

Since 2018, I’ve been writing about strategies to help other city dwellers improve their lives and their finances. To do that, I draw on ancient philosophy, forgotten old books, and ‘80s movies.

2. What deliberate decisions have you made to improve your quality of life? Why did you decide to make these decisions?

First, I need to share a bit of context. Like a lot of people, I fell into my first job. I wasn’t particularly passionate about the field, but I was getting to travel, work on interesting projects, and build skills.

From there, one thing led to the next. I jumped ship from my first job and transitioned to work for one of the company’s clients in San Francisco. I did this primarily because I wanted to leave my home state of North Carolina. I eventually persuaded that team to move me to New York. Then, I switched roles internally to get away from an overbearing boss.

I was making decisions about people I didn’t want to work for and what I didn’t want to do. I wasn’t proactively moving toward what I wanted.

“For many, the big choices in life often aren’t really choices; they are quicksand. You just sink into the place you happen to be standing.”

– David Brooks

I wasn’t choosing my path – I was sinking.

I seldom felt excited about the work I was doing. That went on for the first six years of my career.

At first, I rationalized this away. My path to financial independence was going to be shorter than most. I could afford to continue doing jobs that I wasn’t passionate about as I ran out the clock to early retirement.

After a while, though, this approach caught up to me. I was just trying to kill time on my way to financial independence, but the unfulfilling work was grinding me down. I knew I wouldn’t be able to do this same work until I reached FI.

I was frustrated and bored. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was experiencing burnout as well.

I knew I needed to make a change. I had to try doing something I thought I would enjoy rather than resigning myself to a long, painful slog to financial independence.

In mid-2018, I noticed a job opening on a team I was interested in. It would be a move from a Marketing Analytics role to a Corporate Strategy role, where I would help the firm identify and focus on strategic objectives.

Because the roles were in completely different parts of the firm, I would have to sell the team on my qualifications.

I avoided this kind of risk early in my career. Early on, my fear of failure paralyzed me, keeping me from going after what I wanted professionally. As a result, I spent a lot of time doing work I didn’t care about.

This time, I took a different approach. I chatted with the hiring manager and promptly applied.

After a grueling six-month interview process, a case study project, and a nerve-wracking presentation, I got a call from the hiring manager asking me to meet him in a conference room.

As I walked over, I knew my life was about to change, but I had no idea whether I was being offered a job or let down easy.

I remember my knees shaking as my new manager told me he wanted to make an offer. I was so overjoyed that I accepted before he finished the sentence.

I found it scary to apply for a role that I was deeply interested in but that I had never done before. However, I felt like the path I was on wasn’t aligned with my goals.

I also knew my current trajectory was sure to lead to burnout, frustration, and disillusionment with my career. Instead of letting inertia do its work, I put myself out there and it paid off.

3. How did this career change impact your quality of life?

In short, it feels like I wrested control of my career trajectory from the universe. Previously, I felt like I was “sinking” and allowing my career to happen to me. Now, I enjoy my work and love my teammates. The feeling of doing something that I care about – that I proactively chose – is a new one for me. Taking control of such a big component of my life feels incredible.

With that move came a whole host of other benefits. I got lucky that it paid more, offered more predictable hours, and more closely aligned with the skills I want to build. Because I’m more invested in my work, my job performance has improved.

It’s not that making this career change has solved all my problems. My job is still frustrating sometimes, and difficult coworkers will never go away.

Someone once told me that you don’t ever get rid of your problems, you just get better problems. I’ve found that to be true. I’m much more satisfied with the problems I have now.

On top of the professional benefits, taking this career risk changed how I think about my personal life.

I spent most of my twenties accumulating financial options and flexibility. This focus helped me avoid thoughtless money mistakes but also closed me off to many enjoyable things. Those would slow my path to financial independence.

Emboldened by my success in switching career tracks, I decided to start putting time and effort into things I wanted to in my personal life as well. I didn’t make huge bets at first. Instead, I committed to trying more things I was interested in, even if they “failed” or cost me money.

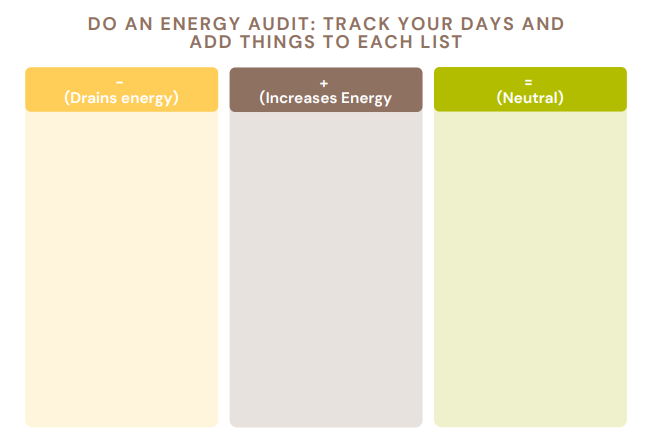

I also had more mental space since my job was no longer a source of frustration. The burnout I was experiencing gradually faded away.

The benefits of this commitment have been huge. In the past two years, I took my blog from an idea to reality and have published more than one hundred posts. I also began a woodworking hobby that has taken me from zero to a reasonably competent furniture maker.

Things haven’t all gone perfectly so far. I’ve written some articles at which I now cringe. I utterly failed in my attempt to build a dovetail box with hand tools. So what? The juice has been worth the squeeze a dozen times over. Even though I sometimes fall short of my expectations, the process of making things has made my life far more fulfilling.

4. How did your career change and pursuing more hobbies impact your financial goals or timelines?

Before this, I would have proudly watched my timeline to reach financial independence grow shorter as my pay grew.

Now that I’m pursuing things I want outside of work, I’ve seen my expenses increase as well. This has slowed my path to financial independence.

For example, doing a few projects in the woodshop annually could cost me about eighteen months between my original financial independence timeline and the one I’m on now. The difference comes to around $2,000 per year – shop time and materials in Manhattan are, predictably, quite expensive – but the enjoyment that I get from the hobby far outweighs the additional spending.

While the studio time and materials are costly, this hobby is extremely fulfilling. I’m typing these answers from a desk and chair that I designed, cut, shaped, and built into finished products. It’s an unbelievably gratifying feeling.

Still, old habits die hard. The idea of willingly slowing down was scary.

There’s a Navy SEAL saying that I’ve found myself thinking about a lot lately – “Slow is smooth. Smooth is fast.”

What the SEALs mean is that in order to do something right the first time, you might need to do it more slowly than someone who’s rushing. Because you are being deliberate, you also won’t make costly mistakes or miss opportunities that you would if you were going as fast as possible.

For example, I could speed up my path to FI by cutting my spending on things I love or moving to a lower cost of living city. But I’m happy with my life today, and I love living where I do. If I moved somewhere cheaper purely for the cost savings, my progress to FI might be faster. But I would be far less happy on the way there. That doesn’t seem worth it to me.

Stoic philosopher Seneca had a great line about this, and one that shows how little human nature has changed in the past 2,000 years. He said that if you stopped a busy-looking Roman on the street and asked them what they were doing or why they were rushing, they wouldn’t know. I’ve always found that haunting.

I could cut my expenses to the bone now to reach FI faster, but I would be doing the same thing that Seneca warned against – hurrying toward a goal for the sake of reaching it.

Instead, I’m choosing to take it slow and enjoy myself on the way there. I have a feeling that I’ll look back and realize that slow is smooth and smooth is fast.

5. What enabled you to make these shifts?

After six years of saving between 25% and 47% of my income, I had a strong financial foundation on which to build. Having financial flexibility made my personal and professional decision-making easier.

That meant my decision to reach for a new job would not impact my ability to pay for my immediate expenses. If I didn’t get it, I could have taken my time to figure out my next move, perhaps even taking a mini-retirement along the way.

I also don’t think I’d have been able to do the things I’ve done without the support of my family and friends, and I’m incredibly grateful for them. They had noticed the toll that my work was taking on me – even before I had – and wanted more for me.

They were very supportive of me taking intentional steps toward the things I wanted in and outside of work from the outset.

My parents, in particular, were my de facto career counselors as I was applying for my current job. They spent hours talking me through my self-doubt and fear of failure as the process went on.

6. Were there things in your life you adapted so you could continue to work toward your financial and life goals?

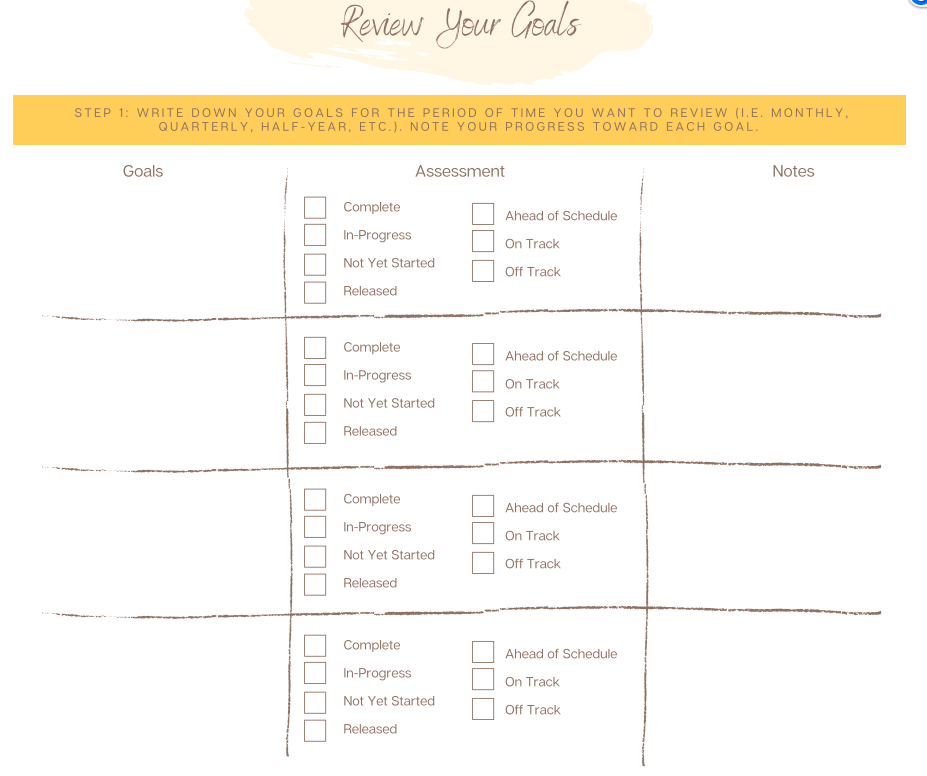

As I’ve become more satisfied with my career and personal life, I’ve adapted my view of what financial independence will look like. I’m less interested in getting to my FI number, retiring, and never earning income again.

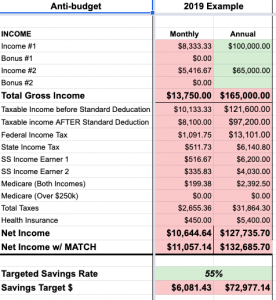

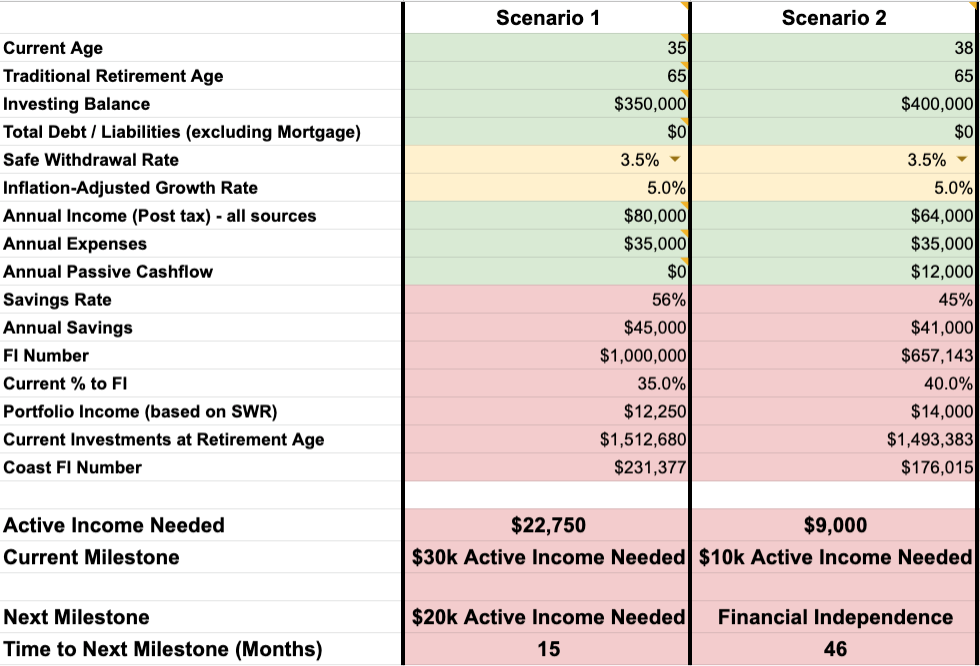

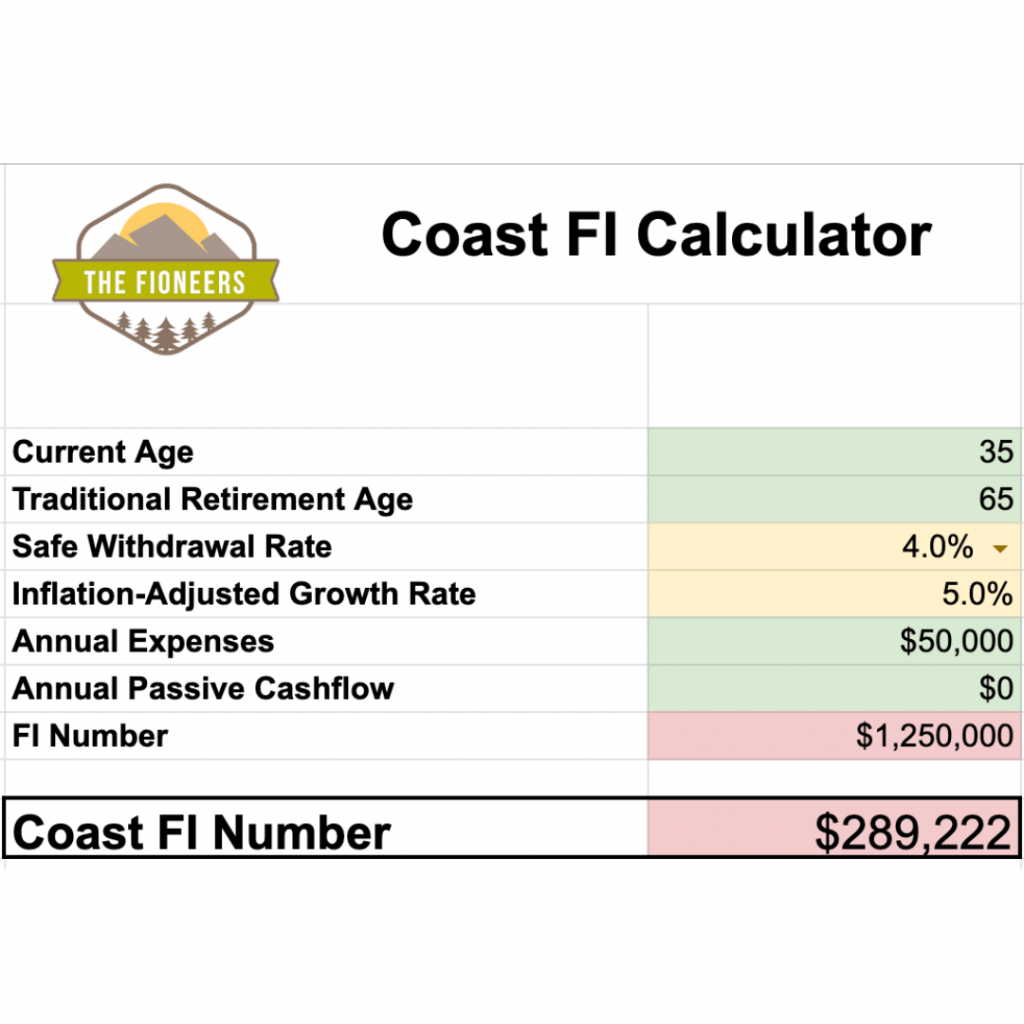

I recently reached Coast FI. For me, Coast FI means that I could earn enough money to cover my expenses for the rest of my career and I don’t need to save any more money. I would be able to retire at 65 with annual withdrawals of 3.5% (a more conservative assumption than the customary 4%). I use a projected asset growth rate of 5% to account for inflation, and I also built a 20% expense buffer into these assumptions. This gives me a lot of freedom and flexibility even if my expenses increase in the future.

I know this is a really great place to be in this early in my career. It doesn’t mean I’ll stop saving, but it means that I no longer need to save as aggressively.

I get to evaluate employment opportunities based on my interest in the work or how well the values of the organization align with my own. I can also make spending decisions based on enjoyment rather than frugality.

That said, I’m still constantly experimenting with ways to trim expenses without sacrificing happiness. I’m not a foodie, so I’ve dialed back my delivery and restaurant spending in favor of high-quality homemade meals. I also canceled my Amazon Prime subscription, which has saved me hundreds in addition to reducing my impulse purchases.

I’ve found that the savings from my experiments help to mitigate the impact of higher spending on hobbies. In other words, being intentional about how I spend in areas I don’t care about has allowed me to more freely spend on the things I do.

7. Why and when do you think someone might consider a shift that will improve their life?

The short answer: Early and often.

It’s much easier to make small moves toward your desired life than one giant, risky, stressful change years down the line.

It’s not necessarily that these small bets are guaranteed to pay off. But I’ve found that ignoring the important things in life will put you in a difficult position later on. And, it’ll be harder and more hazardous to make a change later.

In engaging with the FI community over the past two years, I’ve learned that financial independence is a spectrum rather than a binary choice.

It doesn’t have to be full financial independence or sixty soul-crushing hours per week at a job you hate. There are many potential outcomes between these extremes.

The same goes for your personal life. Many of us can do things we love (or at least enjoy) and still save a significant percentage of our money for an earlier-than-normal retirement. It does require some trade-offs, but I’ve found those trade-offs to be worth it.

To find your place on those spectrums, I’d encourage you to conduct experiments along the way. If you do, you won’t have to make such a substantial change later, as I did.

There’s a quote from Jeff Bezos about his approach to corporate strategy that I think we would all do well to adopt in our personal lives:

“Companies that don’t continue to experiment, companies that don’t embrace failure, they eventually get in a desperate position where the only thing they can do is a Hail Mary bet at the very end of their corporate existence. Whereas companies that are making bets all along, even big bets, but not bet-the-company bets, prevail. I don’t believe in bet-the-company bets.”

– Jeff Bezos

By the time you need to make a “bet the company bet” to make a change in your life, it’s often much more difficult. I can’t tell you how long I spent paralyzed by the notion of making a big change because I hadn’t embraced smaller shifts early on.

If you’re in a similar position, the key to improving your life is starting small. You wouldn’t try to run a marathon tomorrow if you’ve never jogged a mile. Getting more comfortable with conducting experiments is a key first step.

8. What advice do you have for someone considering a similar decision?

There are three pieces of advice I wish someone had given me early on. In fact, someone probably did give me these pieces of advice and I ignored them. I hope there are a few people who will read these and take them to heart.

- Don’t try to run out the clock on your career because your timeline to reach FI would be shorter than average. Life is too short to spend 50% of your waking hours, five days a week, doing something that makes you miserable.

- Make some bets on yourself. Try things you’d like to do, even if they cost you money and slow your path to financial independence.

- Think about life as a scientist would. A scientist is always trying to increase his or her understanding of their field of study by conducting experiments. They have a hypothesis, test it, and see if it works. If not, they haven’t failed – they’ve learned.

We habitually underestimate the cost of inaction and overrate the potential costs of failure. This is why we need to bet on ourselves and conduct experiments.

Trying something that doesn’t work isn’t a failure. Not trying in the first place could be.

I’d encourage you to ask yourself this question. Is it better to arrive at financial independence as quickly as possible, burned out, exhausted, and with fewer hobbies? Or would you rather arrive a couple of years later as a happier, more balanced person?

Thank you, David, for sharing your story!

There are so many things from this interview that I stuck out to me. First, I definitely identified with David’s feeling of “sinking” in his career. This analogy goes beyond drifting or autopilot to explain how firmly rooted we can get into a situation we don’t want to be in if we aren’t proactive. We must proactively identify and move toward what we want.

Sometimes, it seems like people in the FIRE community (and sometimes even the Slow FI community) reject the idea that it’s possible to have a full-time job that you enjoy. David shows us that it’s possible. The lifestyle design option can work for people if they can find the right thing.

When your job isn’t such a source of frustration (even if you work regular hours), you have more brain space to focus on things that you enjoy outside of work.

When we are experiencing burnout, life can feel like a slog. It can feel like our lives revolve around work, preparing for it, recovering from it, and little else. When we get ourselves out of this headspace, we can pursue things in our personal lives that we find fulfilling. It doesn’t require us to retire early.

Having reached Coast FI, David now has the opportunity to:

- Evaluate career opportunities based on his interests and alignment with his values

- Spend money on things that add value to his life

I’ll close the interview with David’s eloquent words: Don’t just run out the clock to early retirement… It doesn’t have to be full financial independence or sixty soul-crushing hours per week at a job you hate. There are many potential options between these extremes.

If you’d like to continue following David’s Journey, you can do so in the following ways:

- Blog: https://Cityfrugal.com

- Mailing List: https://cityfrugal.com/newsletter

- Twitter: @CityFrugal

Great post and interview! My partner and I are so happy to have found your blog as your Slow FI philosophy aligns so much with our core values than many other typical FI blogs. We’ve been on the FI journey for about 7 years and since we found your blog about 6 months ago we’ve had so many more conversations and made a couple large life changes that are more in line with Slow FI. Thank you! Looking forward to more excellent posts and interviews!

Hi Jenn,

Thank you so much for your comment! I’d love to hear about the changes that you’ve made in the last 6 months! Please reach out to us and let us know!

Jess

Hello Jenn,

I have been reading your blog and came across this great interview with David. It really resonates with changes I am trying to make in my career right now. I’m curious if there might be another way to follow/get in touch with David as his blog link and newsletter link are not working.

Thank you,

Caroline

Hi Caroline. It looks like David isn’t blogging anymore. I wish you all the best as you move forward.