I always thought I’d be poor, but I’m not exactly sure why.

I grew up solidly middle-class (perhaps even upper-middle-class). I am well-educated. My suburban K-12 public school system prepared me well for college. I didn’t go to Ivy League schools or anything, but I now have both a Bachelor’s and Master’s Degree. There is no real evidence that this belief of being poor would ever come to fruition.

Except for one thing. In the back of my mind, I wanted to be poor.

Now, this might seem like a strange thing to hear. For some reason, I thought that this was the only unconventional way to live.

I’ve come to realize that money is a tool that helps us live a life aligned with our values. But, it has taken a lot of personal growth for me to get here.

Formative Experiences

During high school and college, I spent as much time as I could internationally. I spent time in Mexico, Ecuador, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Costa Rica. I volunteered at orphanages, built homes, taught at schools, and studied abroad in multiple places. During this time, I was exposed to a lot of poverty. Many of the people, even the professionals, were living on less than $2/day.

To illustrate, I will share a couple of specific experiences that helped to shape my worldview.

While studying abroad in Nicaragua, I stayed with a farming family in the mountains for several weeks. They were a family of 10 people. They lived in a wooden shack that had one bedroom and a large open room for everything else. There was a dirt floor, a detached kitchen with a wood stove for cooking, and no running water. There was one bed. Everyone besides the parents and youngest children slept in hammocks.

Their meals consisted of things they grew themselves. They did the back-breaking work of planting and harvesting all of their food and only had a small amount leftover to sell. In their fields, they grew corn and beans. They had a small garden where they grew a few vegetables. They had cows and chickens for cheese, milk, and eggs.

While I was there, the only things I saw them buy were cooking oil, rice, and soap. The only toilet paper in the latrine was what I had brought with me.

The school in their community only went up to 5th grade. The family only had the means to send their oldest son to live in the city with a family member for middle and high school. Most families in the area did not have that luxury.

Most of the family had never been off of the mountain. The bus fare, which was less than $1, was too expensive. When I first got there, the children were timid around me. When I asked them if they’d ever seen a white person before, they said, “There was a Canadian once who worked in the school…”

After graduating from college, Corey and I lived in another region of Nicaragua that was cut off from the rest of the country. There wasn’t even a road to this region. We had to travel by air or by boat. We lived in a city of 50,000 people that had no city water or sewage. Each house had its own well. Some people had running water (from a pump connected to their well), but most people only had latrines. This was a recipe for parasites and other illnesses.

We taught English at a university there, and we were paid the same wages as the local professors, which was $5 per credit hour per month. Therefore, if a professor taught 4 classes that were 3 credit hours each (for a total of 12 credit hours), they were paid $60/month. In a country where the minimum wage is now around $180/month, the professors often worked additional jobs.

These two experiences made poverty real to me. It was no longer just a statistic or a number on a page.

Guilt and Culture Shock

Whenever I returned from any of these experiences abroad, I was hit with a lot of guilt and culture shock because of my cushy, American lifestyle.

I had an apartment with electricity and running water. The city where I lived provided city water and city sewage.

I had access to high-quality medical care. I lived my life free from parasites and amoebas and didn’t need to take pills to kill them every 6 months.

I had access to high-quality education and many job options. I make over a hundred times more money than university professors in some areas of the world.

There are roads to get me from place to place, and I have a car that will get me there quickly. I have a comfortable bed to sleep in. I could continue, but I think you get the point.

After we returned to the US after teaching English in Nicaragua, I was forced to think about money for the first time in my life. Not only did we move back to the States, but we also moved to a high cost of living area. Finances became an integral part of our life as we tried to make ends meet with two entry-level jobs. At the time, it was amazing to me that the minimum amount to fulfill our basic needs was about $30,000 annually.

While this experience forced me to realize that money was just part of life (bills had to be paid), it didn’t make me feel less guilty about it. $30,000 of necessary living expenses far exceeded the $720 per year that university professors were making Nicaragua, and I didn’t know how to deal with this gap.

At times, the cognitive dissonance was overwhelming. I didn’t feel like I deserved my comfortable life just because I was born into a middle-class American family.

Grappling with my Privilege

Many people frame the feelings that you have upon returning home after an extended period of living abroad as “culture shock” and assume they will go away after several weeks or months.

However, the dissonance has stuck with me. It didn’t merely come because I was different than the people I interacted with. It was because I was privileged in these situations, and the other person experienced disadvantage or oppression.

This video was transformative and helped me understand my privilege.

As a middle-class, white, American woman, I have more privileges than could fill an encyclopedia. To illustrate, I will share a few examples.

- I grew up an America, a very wealthy country with a lot of job opportunities.

- My ancestors were never slaves or discriminated against in education, housing or employment. Therefore, there have been countless generations to build and pass on wealth.

- We were able to more easily rise into the middle class because we benefited from government programs like the GI Bill and red-lining that disproportionately helped white families.

- Because we were middle-class, I grew up in a virtually all-white suburb with an excellent school system that prepared me to go to college.

- I received scholarships, and my parents were able to help pay for my college tuition, and therefore, I don’t have any student loans.

- My family was able to serve as my financial safety net when I first started my career (allowing me to be on their health insurance until 26, to stay on the family cell phone plan, helping pay for medical expenses when I couldn’t pay for it myself, etc.). This allowed me to start building wealth early.

I consider all of these immense privileges that have contributed to the financial position I am in today. These are privileges because they have been afforded to me and my family, not wholly because of our own merits, but because of our demographic characteristics (white, American, middle-class, etc.). These same privileges have not been afforded to many people of color, people who grew up in a developing or underdeveloped country, and/or people who grew up experiencing either urban or rural poverty.

Overcoming the Guilt

It is no surprise that becoming knowledgeable about my privilege made me feel guilty. I do think that guilt is a useful emotion insomuch as it can prompt action. However, guilt and our response to it can also be misguided.

One resource that has been very formative in helping me understand and overcome misguided guilt is an article called “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.”

From this article, I learned that there are two types of privilege:

- Positive privileges are things that we want all people to experience. These are things like your neighbors will be helpful to you, that a demographic characteristic like race or class will not count against you in court, and that you have access to a high-quality education and good job prospects. These things can and should be privileges that everyone experiences, but unfortunately, this is not always the case.

- Negative privileges are things that help to reinforce present hierarchies. Examples of this include the ability to ignore less powerful people, a choice to hire someone who is like me without adequately reviewing the qualifications of all candidates equally (often unconsciously), a college professor assigning books written only by men or only by white authors, supporting policies that disadvantage certain demographic groups.

This understanding gave me a framework to think about all of the things I felt guilty about. I learned that disapproving or feeling guilty about the system doesn’t change it. Action is what matters.

Working to understand the types of privilege that I experience every day is the first step so that I can help with the spread of positive privilege and the toppling of negative privilege.

Me forgoing the positive privilege of making money doesn’t necessarily help anyone else gain these same positive privileges. The only exception is if I have the agency to help spread positive privileges by accepting less.

Re-evaluating the Myth that Money is Evil

There are various unhealthy attitudes toward money. According to Dr. Klonz, we form these money attitudes based on our upbringing and experiences and often don’t question them until later in life, if ever.

It’s no surprise, based on my formative experiences, that I have bought into the Money Avoidance myth. People who buy into this myth tend to believe that rich people are greedy, that money corrupts, and that there’s virtue in not having money.

Beyond wanting to make a difference in the world, my belief in this myth is part of the reason I chose to work in non-profit. I felt like I’d be selling out by working a job where I’d make a lot of money. Little did I know that within 10 years of working in nonprofit, my career would take off, and I’d make more money than I thought I’d ever make in my life.

When this happened, I still ascribed to the Money Avoidance myth, and I wasn’t quite sure how to reconcile my higher wages with my unexamined belief system.

Regardless of whether or not someone has money, it doesn’t make them a good or bad person. It is their actions that must be evaluated. Many rich, poor, and middle-class people make the world a worse place every day.

There are also many, regardless of income, who work to make the world a better place. While not always the case, it’s no surprise that people with more social and economic capital often have broader reaching impacts, positive or negative.

Therefore, as someone who is seeking to make the world a better place, it’s okay (and even good) for me to expand my social influence and economic capital, as long as I am not doing it at the expense of anyone else, particularly those in marginalized groups. This could enable me to make a broader difference in the world.

Debunking Scarcity

Focusing on the broader impact that I can have as an affluent individual isn’t the only major shift that I made to my mindset.

I have come to realize that one of the hidden beliefs that I bought into (without fully realizing it) was that money was a scarce and limited commodity. In other words, that there is a limited supply of resources the world. (Note: I do believe there is a limited amount of natural resources. I don’t believe there is a limited amount of knowledge and human resources. Humans can create immense value out of almost nothing.)

And while scarcity is known for contributing to hoarding behaviors, for me it was different. Because of the international trips and my familiarity with poverty, I found myself shying away from money.

Videos like the one below show the distribution of global wealth, and while there’s value in this message, it presents the world’s wealth as a pie.

I didn’t want to have more than my fair share of the world’s resources, because, in my mind, it was causing others to have less of the pie.

For me, buying into the lie that money was scarce was forcing me to think about the opportunity cost of earning money for someone else.

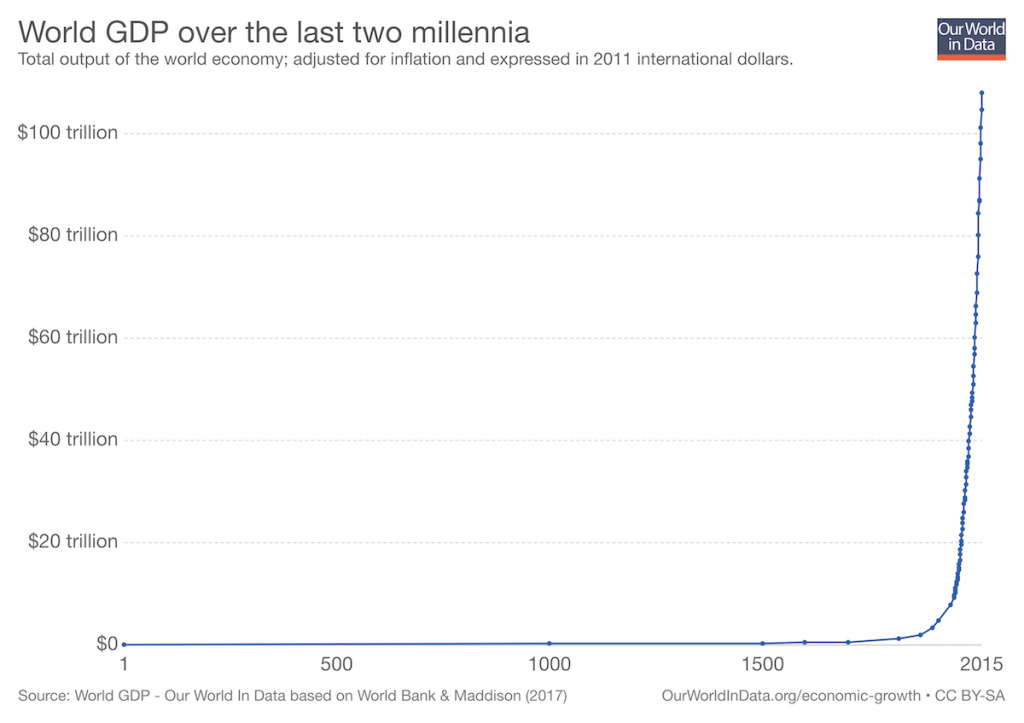

Not only have I come to understand that money isn’t evil, but also that the global wealth isn’t limited. In fact, it has grown over time.

Now that I’ve come to grips with money, what am I doing about it?

This post was tough for me to write. Because money is so integral to life, writing about my views on money is almost synonymous with answering the question, “What is your worldview?”

Coming to grips with money for me is all about understanding and processing the guilt that I felt after returning to the US from my international trips.

I still struggle to reconcile my privileged life with those living in extreme poverty. These experiences will always be like a stone in my shoe – slightly uncomfortable, always keeping me on my toes, and reminding me how fortunate I am.

But it doesn’t mean I need to avoid money anymore.

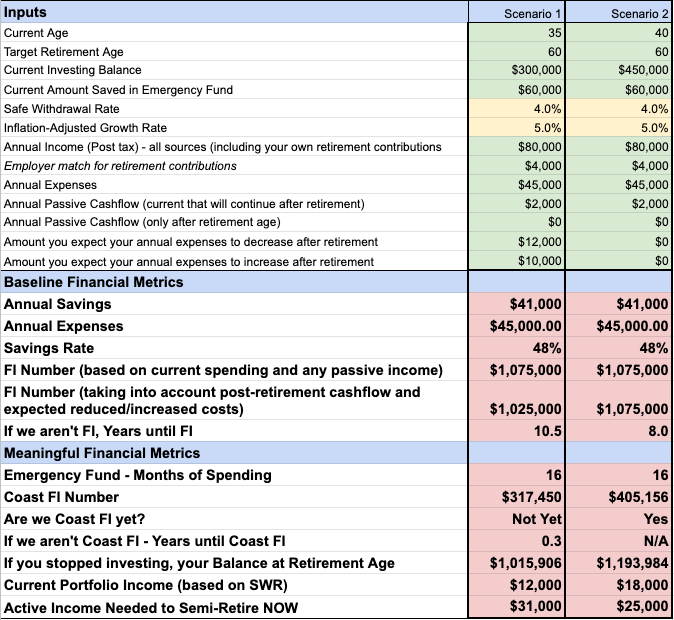

A big part of my new understanding of money comes across in our journey to financial independence.

To me, pursuing FI is not a selfish endeavor. It’s not about making money for money’s sake or to buy more stuff; it’s about making money so that I can have the influence, freedom, and flexibility to make the greatest impact in the world.

Making more money enables me to:

- Choose to work and volunteer in non-profit organizations

- Provide financial support for organizations and causes I believe in

- Support policies that decrease wealth inequality (minimum wage laws, tax-related legislation, affordable housing, affordable health care, etc.), even though these policies might mean that I pay higher taxes

- Using my increased influence within my organization to advocate for and create more equitable systems for hiring, promotion, and retention

- Pursue FI (buy back my time), so I can focus on passion projects that will both make me happy and allow me to make a difference in the world.

It’s important to understand and evaluate our unconscious beliefs about money so that we can live an intentional life and use our money in ways that align with our values.

I believe my FI journey enables me to do this. My FI journey is about living a fulfilling life where I can be happy, healthy, passionate, and make my mark on the world.

How have your formative experiences informed your beliefs about money? How have these beliefs changed over the years?

Thank you for this article and your in-depth thinking about the subject. It’s not easy and raises many questions I have thought about as well. I know my FI journey is much easier because I’m white, but it is hard to see that privilege in daily life without consciously thinking about it.

Hi Ingrid,

Thank you for your comment. I agree it can be hard to notice privilege in our daily lives without consciously thinking about it. One simple thing that I’ve been trying to do is to follow Finance blogs written by people of color. It both helps to keep me grounded in diverse perspectives and the experiences of people who are different than me. I also hope that I can help amplify the voices of people of color by reading and sharing their work with others.

I wish you the best on your journey.

Jessica (aka Mrs. Fioneer)

Thnak you! being an African from a developing country, I really appreciate the humility and insight required to pen this article. We need more people like you in the world. I’m inspired.

Hi Dee,

Thank you for your comment. I appreciate your kind words. It’s something I’ve been grappling with for many years, and I’m excited to have a platform to share what I’ve learned.

Thank you again,

Jessica (aka Mrs. Fioneer)

Thank you for this. I appreciate the honesty and clarity of this post. I came from incredible privilege also (very similar background), but my mother’s constant dismissal of her own wealth as “less than” created a terrible cognitive dissonance within me about money and wealth. I ended up working exclusively for nonprofits (education and mental health), paid way less than I could be paid, but feel the tradeoff power in “meaningful” work. However, I have a strong interest in writing as a career, but you have just managed to explain one of my mental blocks to the self promotion necessary to make money through writing by explaining the “Money Avoidance” mindset. Thank you!

Hi Diana,

Thank you so much for commenting. The cognitive dissonance can be too much sometimes. I think it’s amazing that you work in a mission-driven environment. I’ve always loved working for non-profits as well and the trade-off has been worth it for me. I’m coming to realize that it’s also not either/or. You could both work with a nonprofit and have a career as a writer. I’m so glad you enjoyed the article and it was impactful for you. I wish you the best of luck figuring out your next steps.

I also followed you on Twitter because I’d love to hear where you land with your writing career!

Best,

Jessica (aka Mrs. Fioneer)

Good post Jessica! I’m still working on coming “full circle”. Me and my wife grew up poor but we’ve worked hard to finish college and have 6 figure careers. Slowly guilt has crept in a bit after we traveled the world, as you did. Now we’re sitting at the “action makes change happen” stage, while still trying to enjoy our life. You highlight all those nicely here. I’m sure you’re well on your way to making a lasting and positive mark.

Hi Jim,

Thank you for the comment. This is a hard realization that many people never have. I think it requires us to get outside of our comfort zone to ever realize that there’s a different way to live. I don’t think that enjoying our lives and making change happen are mutually exclusive; I think you can do both. In fact, I think we need to enjoy our lives and be mentally, emotionally, and physically healthy to really be able to help others.

I’m excited to continue interacting.

Jessica (aka Mrs. Fioneer)

I love this, and parts of it hit home. My father has always been poor, and I inherited the mindset that money is evil, and people who have it got it by ripping off others. It took me quite some time to realize that people are people, problems are relative, and bitterness doesn’t put food on the table.

This is a powerful post. I remember being in middle school and telling my classmates people in India were happier than us because they knew how to live with less (I had never been to India but somehow was fixated on other cultures and wanted to be more like them). Excess in America disgusted me from an early age. I’m still not sure where those feelings came from.

I eventually went to Ecuador and saw similar situations as you described in Nicaragua. Even today, I watched a video about a woman in Kenya spending four hours each day carrying water.

I spent a long time wondering if I deserved anything I had because the above situations seemed so unfair. I like how you have given me an example to work through and have put some powerful work into yourself and these beliefs. You and your partner will be great people with your wealth. You can trust that.

As Savvy History commented : this is a powerful post!

I was always hit with the same guilt upon returning from my travels. It took me a long time to process all I had witness from living for several months in Peru.

I wish I had read this article back then and the great resources you’ve highlighted such as: “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.”.

Amazing work and mindset over how money will help you make a great impact in the world. I believe this article is a wonderful example of how you are already making a difference.

Hi Ms. Mod,

Thanks for the comment. I actually didn’t find these resources until the last few years and really struggled with this for many years. It took be a long time to come to grips with the privilege that I have but I wasn’t really sure how to name it or address it.

Thanks for reading. I hope to be able to share this perspective in the PF community.

Best,

Jess

I spent most of my 20s unable to support myself due to a disability. I spent a few years on Social Security Disability, sure I would never be able to work again and would always be poor. Now I have a job where I make a fair amount of money, and it’s still hard for me to reconcile that when I see my tax documents every year. That I make enough.

Now that I divorced my spender husband — who kept us… not financially struggling but definitely kept me from saving nearly as much as I could have — I’m hoping that it’ll start *feeling* like enough as I put more and more money into savings/against the mortgage. Hopefully, one day I can not feel guilty about how much I make and get out of the scarcity mindset. The latter is very important because it’ll help me feel safe contributing to charities, which will do good in the world and also potentially help with some of the guilt.

Hi Abigail,

Thanks for sharing. The scarcity mindset is hard to overcome, and I imagine that it would be even more difficult to overcome if the place you are coming to it is from a place of scarce resources. For me, it was from a place of privilege and working to figure out how to handle the guilt over my privilege. I can only imagine coming to it from a place of poverty.

It sounds like you are doing well now and doing a lot to work through the scarcity mindset. I wish you all the best.

Good luck!

Jessica

I’m late to the party, but this was SUCH a good read. I’m weirdly proud of you for writing it, as it sounds like it was hard. But you’re right. Never let anyone tell you different.

Hi Piggy,

Thank you for your comment! The great thing about writing things like this is that it allows them to really sink in.

Best,

Jessica

Hi There

Even later to the party, but I felt it worth saying – one of the biggest myths I had to overcome was that by me increasing my personal wealth I am removing a portion of the “pie” that someone else could have. This is not how wealth works. We create it all the time, and add value to things that previously had no value. Purposefully avoiding wealth creation is the only way to really impact the size of the “pie” because now what I contribute won’t benefit anyone.

As an example, think about sand. 100 years ago, sand was basically just really grainy dirt. It had no purpose. Now the entire world runs on it, and silicon chip manufacturers are some of the most profitable businesses in the world. If responsible people grow wealthy enough to make a difference, it will only increase the possibilities for the people in the world living on $2 a day.

I’m so glad that you’ve been able to reconcile a tough issue, and kudos to resolving to leverage your privilege into helping those in the world who are less privileged.

Michael

Hi Michael,

Great to hear from you! It’s amazing how our perspectives can change when we work through these money myths. I can completely identify with you. I felt guilty for making money because I thought it meant that someone else would get less. I agree and now realize that just isn’t how it works. I like how you said that by adding value to things, we can hopefully lift others up as well.

Thanks again for the comment,

Jessica

Such great perspective. It’s amazing what being around people with so little can make us appreciate in our day to day lives. How often do we in the US step back and realize that we are living in one of the more prosperous countries in the most technologically advanced times in history? Thanks for the reminder and it’s posts like this that help keep us grounded.

Thanks for the comment! It definitely keeps me grounded.

Soooo absolutely on point! You’ve said what i’ve been thinking for years! Well done!

You mentioned helping to change society I believe the government can also do this via its policies. Please follow @StephanieKelton & her book ‘The Deficit Myth’.

Basically governments can provide free education/healthcare/legal help via economics. Hopefully people will at least look into this & investigate before making up their minds.

The conclusion I’ve come to as an ethnic minority, to overcome ‘institutional racism’ we have to first ask companies to change

‘why aren’t there any ethic minorities on the board level?’

‘Could they start to promote & train them up to this level? As I’m a client of yours I would appreciate if you could look into doing this, sooner than later…..’

If this doesn’t work then we advise ethnic minorities to take companies to employment tribunals (that’s what it’s called in the UK).

By becoming FI (& loads of ethnic minorities as well) we can influence this via solicitors/law firms, accountancy firms, Ivy League colleges etc. We’ll become a powerful entity.

Hi Fay,

I completely agree with this! I definitely think that governments should provide all of those things. And, that when we build financial freedom, we can better influence change.

Thanks for your comment,

Jess

Thanks for writing. I’m curious to know your thoughts on why we’ve seen a rash of white women in the media called Karens judge others, especially minorities.

Just wanted to get your perspective on this phenomenon. What do you think is going on in these womens’ heads. And is recognizing one’s privilege enough?

Going from highlighting you will spend $100,000+ camper van to this post is quite a juxtaposition.

But what more can we do to help others, like you did when you were younger as a English teacher?

Thanks

Hi Shawnny,

Great questions and this is something that’s taken me a long time to work through. Let me try to share how I reconcile all of this for myself.

First, my thoughts on “Karens”. I think “Karens” have always been out there doing exactly the same things that they are getting called out for now – it’s just that people are now more comfortable and have the power to be able to call them out. Like the “me too” movement, I’m happy that people are calling out bad behavior – sexism, racism, classism, ableism, etc. much more often.

Honestly, I’ve worked with my fair share of “Karens”, and while I can’t know what’s going on in their heads, one commonality was that they didn’t have significant experience spending time with people who were very different from them. Or, they themselves would equate the sexism that they experienced as a white woman with the level of sexism that women of color or women with disabilities have.

Now onto the question of if recognizing one’s privilege is enough. I don’t think recognizing one’s privilege is enough.

I think it’s important to recognize our privilege and determine which privileges are positive privileges (i.e. the things we want for ALL people) vs. negative privileges (i.e. ways that I experience advantages particularly because someone else experiences a disadvantage).

Then, I need to take action. How can I take action to reverse negative privileges? How can I take action to try to get positive privileges extended to more people?

As a note, I know that I cannot carry the weight of the world on my shoulders, but I do know I have a part to play in my own small section of the world/internet. This means I can do things like: support policies (and politicians) that would help all people (particularly women and people of color) get to a point where they can not only survive but also thrive. Policies like this would include: increased minimum wage, affordable healthcare, paid parental leave, childcare subsidies, universal pre-K, affordable housing, student loan forgiveness, etc. These policies would have far-reaching impacts that I could never make as an individual.

But, it’s also important for me to take action on an individual level as well. When I was employed in a traditional job, I was a leader in equity and inclusion efforts in my workplaces – focused on increasing diversity in hiring pools, creating a fair and equitable rewards and recognition system, and helping the organization be more understanding and embrace differences. Now, in my current role as a blogger/coach, I make sure to lift up the voices of people from different backgrounds. It’s important to ensure that we have a variety of different perspectives from all walks of life. I also will call out racism, sexism, ableism, etc. when I see it – if someone uses slavery, hetero-normative, or ableist language, I’m going to call them out on it and do my best to educate them about why. In addition to that, I give to causes that matter to me.

All that to say, No, I don’t think acknowledging our privilege is enough. We must also take action.

Now, let’s talk about spending $100,000k+ on a campervan. I feel good about this. My past self would not have. What’s changed? I no longer feel like I need to be a martyr to assuage my guilt. I can do things (and buy things) that will make me happy and are in accordance with my values. I can do things that will help me thrive. In fact, I believe that everyone deserves to thrive (that’s a positive privilege I want everyone to have).

As a woman with a history of severe depression and anxiety, I know that there’s a balance to be struck between focusing on your own life and happiness and the needs of others. I also know that one of the best things that I can do for other people who have experienced mental health issues is to live by example. Making decisions that will help me thrive has inspired so many others to do the same. I don’t say this to brag… only to say that I’ve heard from so many readers and clients that me doing things like this has made them feel a bit more empowered that they could do the same. And you know what? Many of these people have experienced disadvantages in some way – whether it be because of their race, class, ability/disability, mental health challenges, etc., and they deserve to thrive. We all do.

Please let me know if you have any other questions. I’ve tried to answer these thoroughly, but I’m sure there’s more to discuss.

Best,

Jessica