I used to spend money without even thinking about it.

I used to spend money without even thinking about it.

I’d grab a coffee on my way into work because I didn’t like the Keurig coffee in the office. I’d grab lunch from the cafeteria in my building because I was too lazy and tired to make lunch in the morning. We’d say yes to everything our friends invited us to, even if we didn’t really want to go.

We’d eat out and order in on weeknights because we were too tired to make the dinners we planned, and then, we’d let food go to waste.

I’d buy clothes when I felt like it or when I was bored. I’d buy books off Amazon instead of borrowing them from the library.

It was $3 here and $10 there and $50 there. Since these were small purchases, I didn’t think twice.

When I was introduced to Financial Independence, I started to think about money in a different way.

The concept that completely shifted my paradigm was that instead of using your money to buy stuff, you can use your money to buy back your time.

This mindset shift changed everything for me, and I began to be more intentional with my spending as a result of a new mindset.

Two Hacks to Change Your Spending Behavior

1. Calculate your Real Hourly Wage

The concept of being able to buy back your time with your money was first introduced to me in Your Money or Your Life. In the book, Vicki Robins says, “Money is something that we choose to trade our life energy for.” Said, in another way, “you ‘pay’ for money with your time.” Therefore, when we use our money to buy stuff, we’re ultimately paying for it with our time.

At first blush, this is a very abstract concept, but it is possible to operationalize by calculating your real hourly wage.

Your Real Hourly Wage = (Total weekly earnings – Total weekly job associated costs)/Total weekly job-related hours

While this entire concept is explained in the book, you can also find the Life Energy Calculator on the website to calculate your real hourly wage.

Let’s take an example. Say Jenna earns $78,000/year. This means that she earns $1500/week (before taxes).

Jenna also has other costs associated with her work:

- She commutes using public transportation which costs her $25/week.

- Jenna’s job requires her to wear business attire on a daily basis, and she, therefore, spends about $520 more per year on clothing than she otherwise would (equating to about $10/week).

According to Vicki Robin, there are other costs like daily decompression with alcohol or escape entertainment, vacations, and job-related illness, but I am going to keep these out of the calculation for simplicity.

If you were only looking at dollars earned for hours worked (assuming 40), you’d think that Jenna made $37.50/hour. However, it’s not that easy.

We also need to take into account the actual amounts of time that Jenna spends at work and other job-related time.

Because Jenna has a fairly demanding job, she works approximately 47 hours/week, far above the typical 40 hours for a full-time employee. She commutes for 30 minutes each way, adding 5 hours to her total work-related hours for the week.

If you enter all of these things into the calculator on the website, which also calculates taxes, you’d see her real hourly wage.

After you calculate her real hourly wage (subtracting taxes and expenses and adding her additional hours and commute time), you realize that Jenna’s true hourly wage is almost $20/hour less than you might have thought.

That’s a sobering thought.

The value of this tool is that Jenna now knows that if something costs $20 it is equal to one hour of her work time. Thinking about the tradeoffs between time and money now become a lot more concrete.

- Buying a book from Amazon (that she could borrow from the library), will cost her an hour of her time

- Buying coffee three times/week ($10) for a year ($520) will cost her about 26 hours of her time

- Buying a new (to her) car for $10,000 will cost her 500 hours (approximately 10 weeks) of her time.

This simple way of thinking about tradeoffs has helped me think more critically about my spending decisions.

Why Calculating your “Real Hourly Wage” is so Helpful to Stop Spending Money

The real hourly wage is helpful because it helps us to understand that we are “paying” for money with our time and energy. Therefore, when we spend money to buy goods, services, or experiences, we are really spending our time.

One misconception of the “time is money” paradox is that some use it as a justification to spend more money. For example, Jenna could say, “if I can pay someone to mow my lawn for $20/hour, that is worth it to me because my hourly rate is $37.50/hour (although we know that her real hourly rate is actually much lower).”

What this logic fails to recognize is that in order to pay someone $20 to mow her lawn, Jenna must also work one additional hour of her job to pay them. Either way, she is working an hour to pay for the lawn to get mowed.

The real hourly wage also helps us to understand the hidden costs (in both time and money) associated with our jobs.

Many of you know that I took a “pay cut” earlier this year to work part-time. While this pay cut is a reduction in total pay (given that I’m working many fewer hours), it only appears to be a reduction in my pay rate.

When I calculate my real hourly rate using Life Energy Calculator, I realize that my hourly rate for the part-time role is actually $5/hour more because I am working less (unpaid) over time and have a shorter commute.

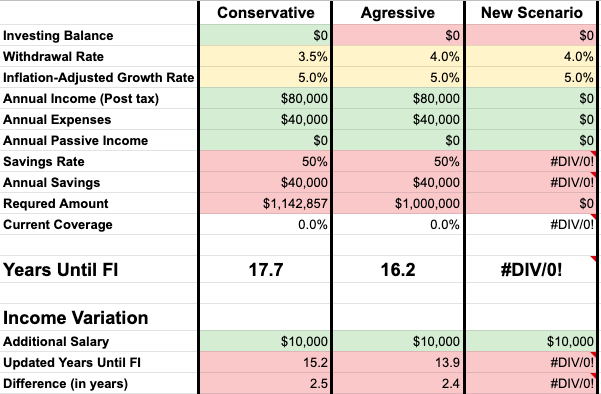

2. Consider Long-Term Opportunity Costs

What the true hourly wage approach doesn’t take into account is the long-term opportunity costs of spending the money now versus saving this same money over the long-term.

When you begin to incorporate the compounding growth of savings into your framework, it challenges your spending habits and helps you identify your values.

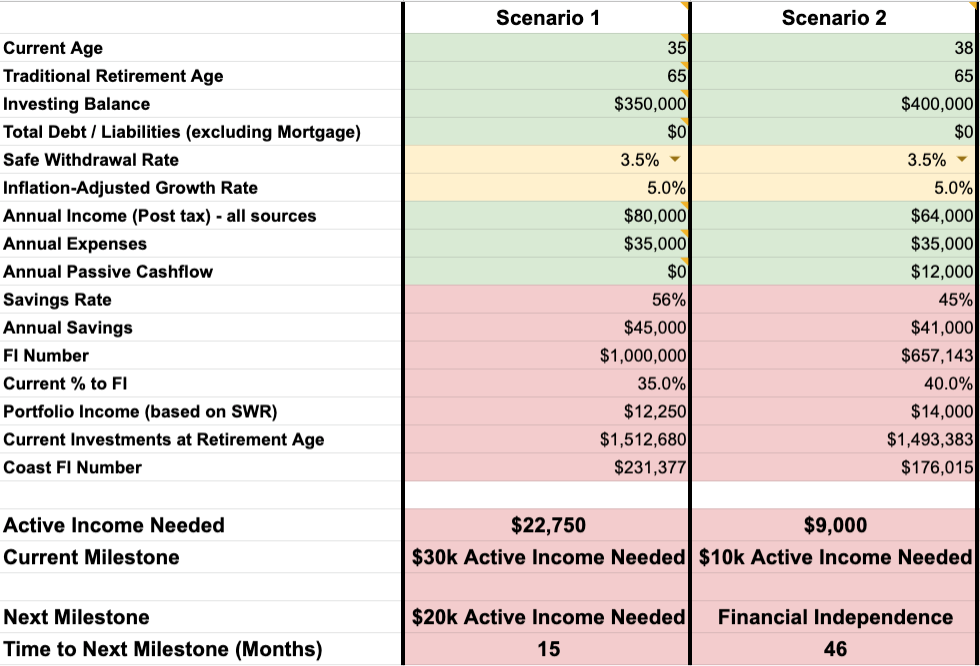

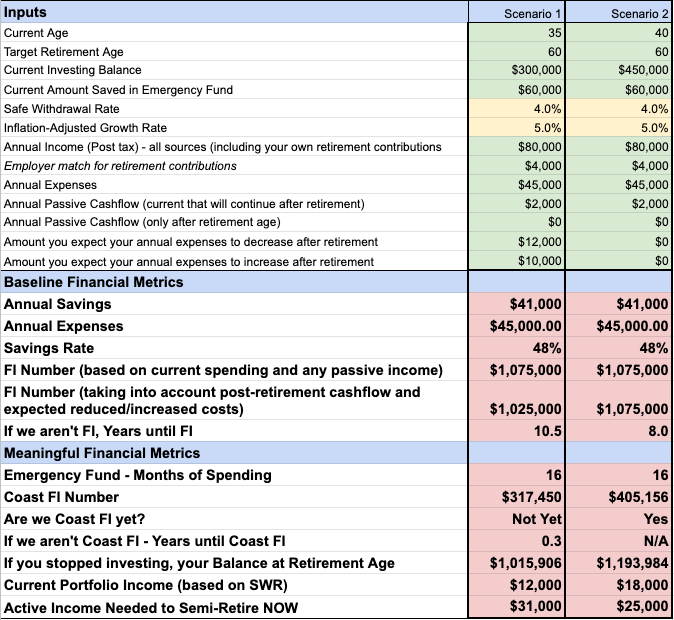

One tool that’s very helpful to help us think through long-term opportunity cost of spending or saving money is the Pretirement App. This app does two very helpful things:

- It tells you your baseline for how long it will take to achieve Financial Independence by putting in some basic information into the app.

- It, then, allows you to try out “what if” scenarios of spending or savings to understand how much it would impact your timeline.

The reason why I love this approach so much is that it doesn’t just tell me the calculation in dollars.

For me, knowing that a certain decision would shorten my mandatory working career by a certain amount of time is much more motivating than giving me a number of how much my investments would be worth after a certain number of years.

By telling me how much time it would take me to achieve Financial Independence, it makes the decisions feel much more real and important.

I know each person is different, so if you think you’d be more motivated by understanding the dollar amounts, there are various online compound interest calculators that you could use instead.

Selling vs. Keeping our Old Car

A couple of years ago, Corey and I bought a new (to us) car, replacing a car that we’d had for about 8 years. We briefly considered keeping it as a second car.

At the time, I drove our one car to work, and sometimes it was inconvenient for Corey to wait for me to get home to go and do something after work.

In this table, you can see the costs associated with this single decision. We put these costs into the Pretirement app to help us understand the impact of the decision.

| Item | Cost | Long-term Timeline Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Keeping the Car (instead of selling) | $3,000 (once) | 1/2 month |

| Car Insurance | $1,400/year | 4 months |

| No longer renting out our 2nd parking spot* | $200/month ($2,400/year) | 6 1/2 months |

| Maintenance for a 15-year-old car (knowing there will be issues | ~$500/year | 1 1/2 months |

| Total | 12 1/2 months |

*Yes, we do rent out our second parking spot to a neighbor for $200/month. It’s a benefit of living in a big city with limited parking.

There are other costs associated with keeping the car that I didn’t include on the list (registration cost, extra gas, etc.). Even without these hidden costs, keeping a crappy 15-year-old car would have meant that we’d reach FI a full year later than our baseline of 10 years. It would have meant increasing our timeline by over 10%.

Not surprisingly, that didn’t seem worth it, and we sold the car.

Food Spending

It’s natural to think through large spending decisions like a home or a car, but this can also apply to smaller spending decisions.

Let’s think about how I used to buy coffee and lunch every day at work.

Coffee = $2.50/day ($12.50/week)

Lunch = $10/day ($50/week)

Total cost/month = ~$270/month or $3,250/year

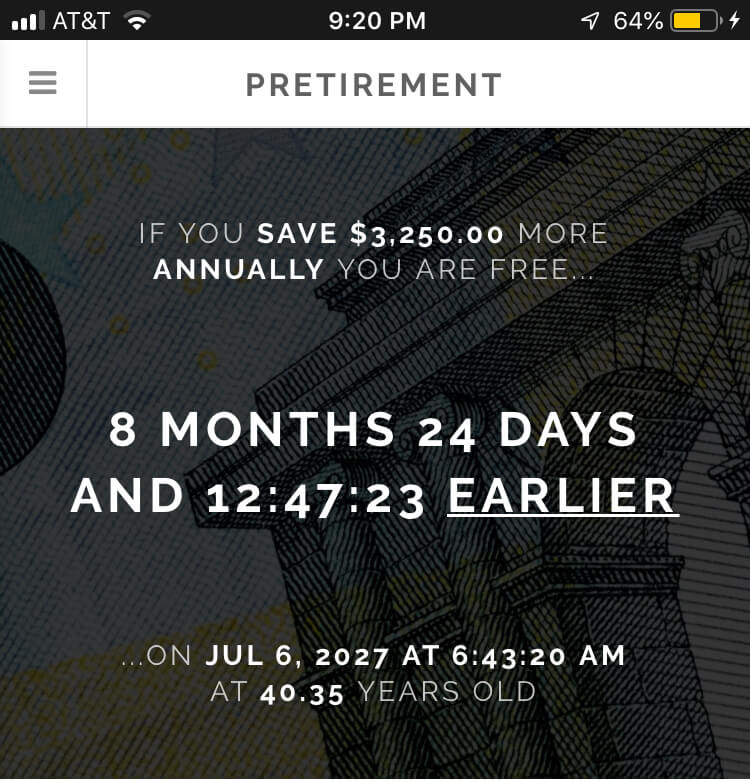

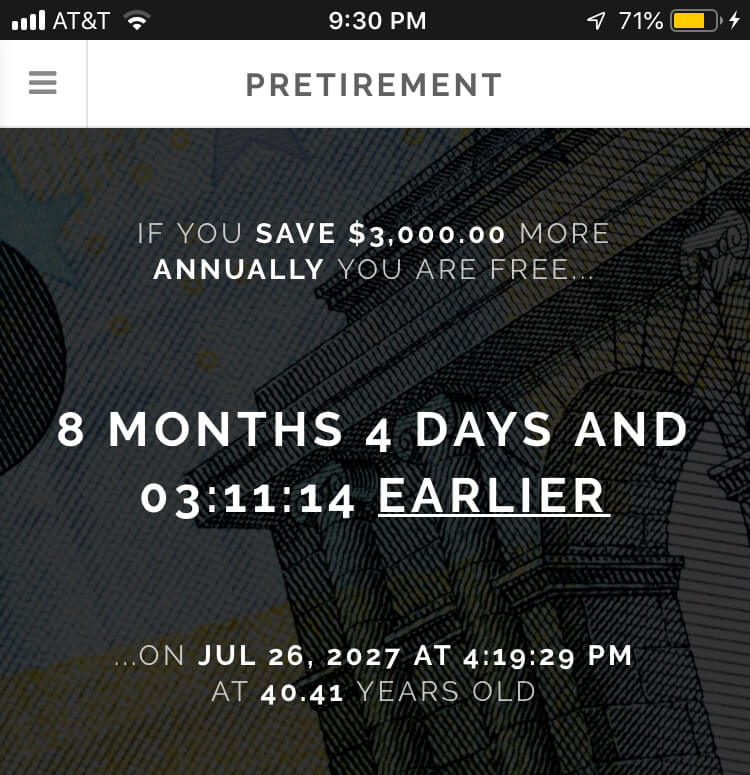

If I put that information in the Pretirement app, it shows that making the small decision to make coffee at home and bring lunch to work means that I could reach Financial Independence almost 9 months earlier.

Now, let’s put that in context of our larger food spending challenge. In mid-2018, Corey and I challenged ourselves to cut our food spending from an average of over $6/meal to about $3.50/meal.

By eating out and order in less, buying in bulk, meal planning, and not letting food go to waste, we cut our food expenses to about $3.25/meal.

This now saves us about $500/month, so the intentionality went far beyond coffee and lunch.

The Pretirement App shows us that this decision allows us to reach FI almost a year and a half earlier. These simple changes have shortened our timeline to reach FI by about 15%.

Travel

Now, let’s think about a medium-sized purchase: travel. It’s not as big as buying a house or a car, but certainly bigger than buying a coffee.

I absolutely love to travel, and therefore, I don’t mind spending money on it. In fact, I’d be willing to work longer to be able to travel the world.

However, by making some small changes in our lives, we’ve been able to cut travel expenses significantly while still being able to travel the world.

We used to pay for most of our travel costs out of pocket, usually spending about $2,000-4,000/year. Now that we are avid travel hackers, we spend a few hours every few months to determine the best credit cards to get that align with our upcoming travel goals.

Through travel hacking, we are able to cover most of the costs for 1 large trip/year and flights and/or hotels for a few smaller trips per year, savings us the $2,000-4,000 we would have otherwise spent.

In 2019 alone, we will be using credit card rewards to cover our entire trip to Panama (round trip flights, 8 nights in hotels, activities, and travel within the country) which we have projected will save us about $2,500.

We will also use points to fly to visit family, to go to an out-of-town wedding, and to attend Fincon in September. For this ad hoc travel, travel hacking will save us about $1,000-1,500.

Within one year we’ll be saving $3,500-4,000 in travel expenses, just by strategically using credit card rewards. Let’s assume this is higher than normal and our average savings per year on travel would be about $3,000.

If I put this into the Pretirement App, you will see that this small shift allows us to reach Financial Independence about 8 months earlier.

Why Understanding Long-Term Opportunity Costs is so Helpful to Curb your Spending

The most helpful thing about opportunity costs is that it encourages us to take a long-term view. At this moment, I might really want to but coffee for $2.50, and it might seem worth the minutes of my time that it would cost to make up the cost.

However, understanding opportunity costs encourage us to think not only about today’s coffee, but about how much every coffee will cost me in a month, a year, and in my lifetime if I were to save the money instead.

Then, I think bigger.

If this one decision is incorporated into a long-term food spending plan, where I save an additional $500/month by reducing all of my eating out expenses (including the coffee), that is significant savings, reducing my time to reach FI by 10-15%.

Opportunity costs help us to understand that coffee is way bigger than just coffee. It helps us to understand the long-term implications of our decisions, big and small.

Financial Independence is NOT about Deprivation

While I am certainly focused on reducing my spending so that I can reach Financial Independence more quickly, I think it’s important that we don’t approach our pursuit of FI with a deprivation mindset. Instead, I’m using these frameworks to approach my spending decisions with more intentionality.

If there are things that don’t add value to my life, I do not want to spend my hard-earned money (and the time I spent making that money) on them.

If I can borrow a book from the library instead of buying it, great! If I can sell a car I don’t need, great! If I can bring my lunch to work and make coffee at home in the morning, great! If I can minimize my travel expenses with travel hacking, great!

What you don’t see in this list are things that I believe would truly add value to my life. If there’s something that will, I might intentionally decide that it’s worth spending money on.

I still spend money going out with friends because that is something I value. Would I be able to reach FI faster if I didn’t? Probably, but it isn’t worth it to me.

I bought an $800 wide-angle camera lens this year because I didn’t previously have one. Not buying this would have decreased my timeline to FI slightly, but I love photography, so this purchase was worth my “life energy.”

If we moved to a lower cost of living area or lived further outside the city so that we could have a less expensive home, it would also shorten our timeline to reach FI. However, the longer commute time and the distance to our friends would not be worth it to us.

These two frameworks help us to think more intentionally about our spending. We are constantly asking ourselves these questions:

- Is this worth my “life energy” (i.e. time)?

- Is this worth the long-term impact on my FI timeline?

Whether the answer is yes or no, these questions allow us to be more intentional with our money and thus, our time.

Great post. I’m a big fan of playing with your mental scripts to effect behavioral changes.

First one: I love YMoYL! However, I have a hard time with the first point because I think it’s important to factor in nonsalaried benefits. I have significant life and disability insurance through my employer, and a pension. My (necessarily comprehensive for my regular medical care) group health insurance plan would not be accessible to me at the rates my employer pays; to really compare, I would have to price individual plans/self-pay for similar coverage. I’m scared to do these calculations because it might cause me to THINK I have more money than I do. Hahaha.

The second one is helpful for delayed gratification once you are out of debt and can invest more (I’m not there yet). Great motivation; I think I’ll come back here when I’m out of debt & considering if I should try for FI/RE. (I always will try for FI and plan to be retired before 60–which is earlier than most people my age plan to retire).

Hi Diana,

Thanks for your comment. You make a great point around the non-salaried benefits of working. I wasn’t factoring in insurance, 401k matching, pension, etc. I think there’s a ballpark that those things are worth ~30% of your salary, so I think you could take your “real hourly rate” and add 30% to it. I wasn’t thinking about that. When I’m comparing 1 job with benefits to another job with benefits, I’m comparing apples to apples. But when I’m comparing a job with benefits to one without or self-employment, it wouldn’t be apples to apples comparison, so I appreciate you bringing this up.

I agree the second one is helpful. I think of it less as delayed gratification and more about intentionality. I don’t feel deprived because I’m not buying the coffee. Instead, I feel excited that I’m putting my money where I want it to go.

Thanks again!

Jessica (aka Mrs. Fioneer)

What website is it you’re using that displays how many days you have left to FI? I particularly liked how it broke down how many years you have left. Super fun and cool!

Hi, I’m not sure if you can find the same information on a website, but you can download an app. It’s called Pretirement; you should be able to find it in the app store. I honestly don’t know who made it, but it’s a great app!

Hi Jessica,

Great post. I also loved the idea of being able to calculate how much a single decision/purchase could put you off of your FI goal in months/years. It doesn’t seem like that app is available anymore though. I know you posted this about a year and 8 months ago, but wondering if you still have that app or have a new link to find it?

Question: I tried locating the “Pretirement app” in the App store and nothing is coming up. Is it called something different?

Unfortunately, the app no longer exists, and I haven’t found a good alternative.